Childhood Trauma and Brain Development

Studies show that a range of traumatic experiences in childhood, including abuse and neglect, lead to several key changes to the development of children’s brains. Our latest blog looks at the effect this can have on a young person's behaviour.

Researchers at the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families highlight that groundbreaking recent research into childhood trauma and its impacts on brain development is often locked away behind pay walls in academic journals. This leads to gaps in knowledge which the Centre aims to address.

Studies shared by the Centre demonstrate that a range of traumatic experiences in childhood, including abuse and neglect, lead to several key changes to the development of children’s brains. These developmental differences give rise to a phenomenon called ‘latent vulnerability’, which refers to the link between childhood trauma and increased rates of mental ill-health.

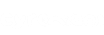

The three primary changes seen across brain areas are detailed below.

1. The Threat System

This brain system helps us to detect and respond to danger. Exposure to ongoing abuse or neglect can lead to long-lasting changes in this system which can lead to hyper-vigilance (or being highly alert to threat) or excessive avoidance of threats. This effect can interfere with children’s ability to make friends, concentrate, and navigate ambiguous social situations. Sometimes children misinterpret neutral, friendly behaviour or conversation as threatening, leading to avoidable conflict.

You can find out more about how growing up in a threatening environment can affect brain development in SCCR’s The Learning Zone.

2. The Reward System

Rewards (or everyday positive experiences such as cuddles, smiles, and food) are often inconsistent in neglectful and abusive childhood environments. This can lead to children’s brains being less reward-sensitive. This brain adaptation, while protective in an abusive or neglectful environment, has been linked to long-term difficulties in functioning. These include a reduced ability to experience pleasure, difficulties in social relationships, and an increased risk of depression.

3. The Memory System

Our memory systems are important for learning new things, recalling past experiences to help solve novel problems and make decisions, and developing a sense of self. Studies show that physical abuse and neglect can lead to ‘over-generalisation’ of memories, where everyday memories are less detailed. Such traumatic experiences have also been linked to decreased activation in brain areas associated with memory recall around positive experiences and increased prominence in negative memories, or a tendency to focus on negative memories and thoughts.

The above brain adaptations are thought to have evolved as a protective mechanism to keep children safe while in danger. However, when children are not in an abusive or neglectful environment, such changes can make everyday life more difficult. This includes their ability to engage and learn in classrooms, to make friends and connect with others, navigate predictable environments such as a secure foster placement, experience pleasure and regulate their emotions, and more.

These brain changes can have a huge impact, but future outcomes are not set in stone, and with support and a safe, stable environment, children can learn to build resilience and thrive.

If you’re interested in emotional coping strategies for young people, click here, and if you’re a professional who works with families, click here.

Stay up to date with the SCCR for further information and tips on how practitioners can help support children and young people who have been affected by trauma.

You can find our more by visiting The UK Trauma Council website and by reading their practitioner guidebook.

The UK Trauma Council website: https://uktraumacouncil.org/.