How to Create More Trauma-Informed Responses in Schools

Last week we were honoured to be joined on World Teachers Day by nurture lead Gerry Diamond, who spoke about creating trauma-informed responses within classrooms. Here’s a summary of what Gerry communicated during his event.

How can educators provide a nurturing and supportive environment that helps young minds heal rather than perpetuating the cycle of pain? In this blog, we'll explore the concept of trauma-informed responses in classrooms, understanding that trauma doesn't happen in a vacuum. It often arises from intergenerational trauma, and the human brain is profoundly shaped by its environment.

Imagine a flower that refuses to bloom. You don't blame the flower; you examine its environment. Trauma operates similarly. Young people who exhibit challenging behaviours may not be inherently ‘bad’ or ‘broken’. Instead, their environment might be hindering their growth. Just as you'd adjust soil, light, and water for a flower, we must modify the classroom and school environment to nurture emotional growth.

Trauma isn't isolated to one individual; it can be passed down through generations. Parents can unconsciously transmit their trauma to their children. What may seem ‘abnormal’ to outsiders could be the only reality these young people have known. We must acknowledge the deep interplay between family dynamics, community influences, and individual experiences.

Neuroscience is key here. Our understanding of brain development has evolved; it’s not merely a process of growth – it’s about building connections within the brain. Social interactions and environments significantly impact how the brain develops. To foster healthy brain development, we must provide a nurturing atmosphere that encourages learning and emotional growth.

To heal young people, we must heal families and communities simultaneously. Isolation doesn't lead to growth. Young people should be empowered to become their own stress detectives and trauma detectors, helping them understand their experiences and emotions better.

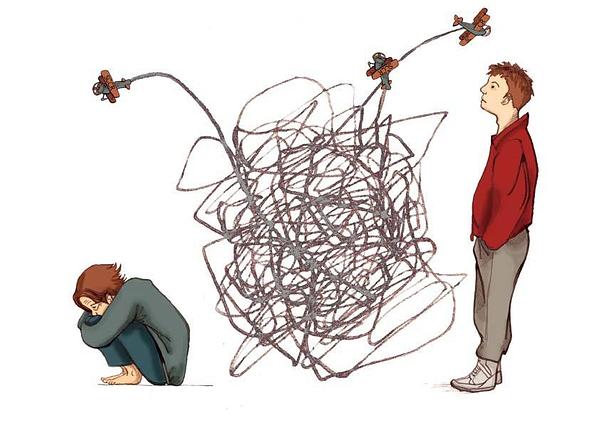

"It's Not What's Wrong with You, But What's Happened to You." This statement embodies a profound shift in perspective. Instead of focusing on what's "wrong" with a young person, we should ask what has happened to them. Trauma can stem from past experiences or even something that occurred earlier that day in school. Our role as educators is not to "fix" them but to create a refuge of sanity where they can heal and thrive.

You can't punish trauma out of young people; doing so only adds to their pain. However, this doesn't mean there shouldn't be consequences for actions. Instead, it means we must understand their stories and experiences to formulate a plan that helps young people return to themselves and develop positive behaviours.

To effectively address the challenges young people face, we must go upstream and be curious about the roots of their behaviours. Every behaviour has a story behind it. By understanding these stories, we can tailor our responses and support accordingly.

Teachers may not be able to regulate a child's developing brain, but they can build relationships. These ‘micro-moments’ of connection, such as giving a compliment, are powerful tools for strengthening relationships. When students feel seen and valued, they are more likely to engage positively in the learning process.

Instead of punitive measures like ‘time-outs’ for misbehaviour, offer young people ‘time in’. Create space for them to talk, fostering a sense of ‘me with you rather than ‘everyone against me’. This approach opens up healthy and supportive conversations, allowing students to express themselves and their needs.

Being trauma-informed is not enough; we must also be trauma-responsive. Our classrooms can become sanctuaries of healing, where young people are not punished for their trauma but are instead supported in their journey toward recovery. By understanding the roots of their behaviours and building strong relationships, educators can play a pivotal role in helping young hearts and minds flourish.