Professionals and Practitioners

This digital resource tells the story of how our brains interpret the world around us and how this translates in our bodies, emotions and behaviours. It has been designed to be used by professionals working with young people interested in learning more about the science of conflict and boosting their wellbeing.

Emotional Regulation and Unhelpful Emotional Expression

Summary

- Emotions can become problematic if they become dysregulated.

- Emotional regulation is our ability to maintain a level of emotional arousal that we feel in control of and able to cope with.

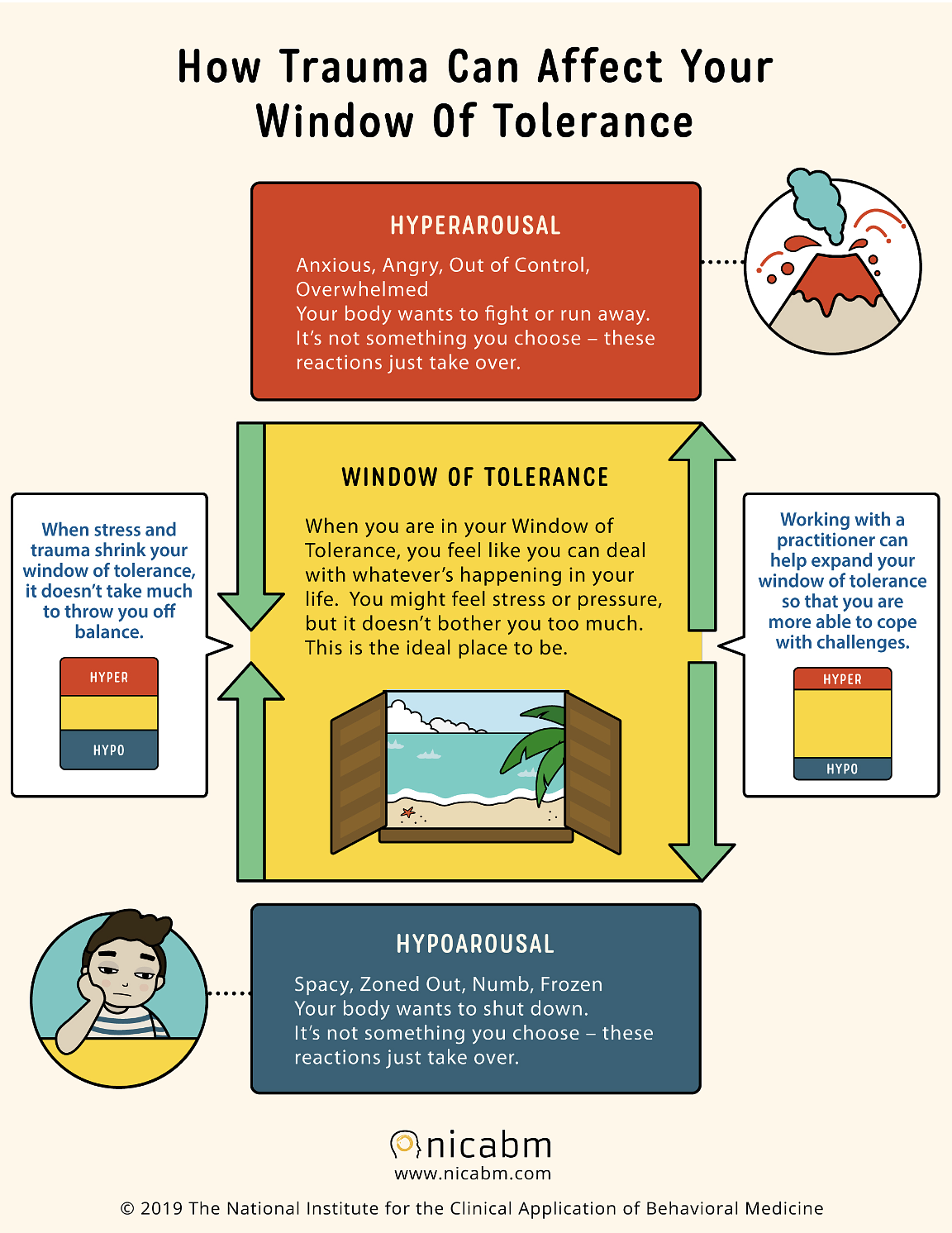

- In Dr. Siegel’s “window of tolerance”, hyperarousal indicates under-regulation of emotion causing you to feel overwhelmed. Hyporegulation is over-regulation of emotions causing you to feel numb and shutdown your emotions.

- In our window of tolerance we feel in control and able to cope with our emotions. The window of tolerance can grow and shirk and is influenced by long- and short-term factors.

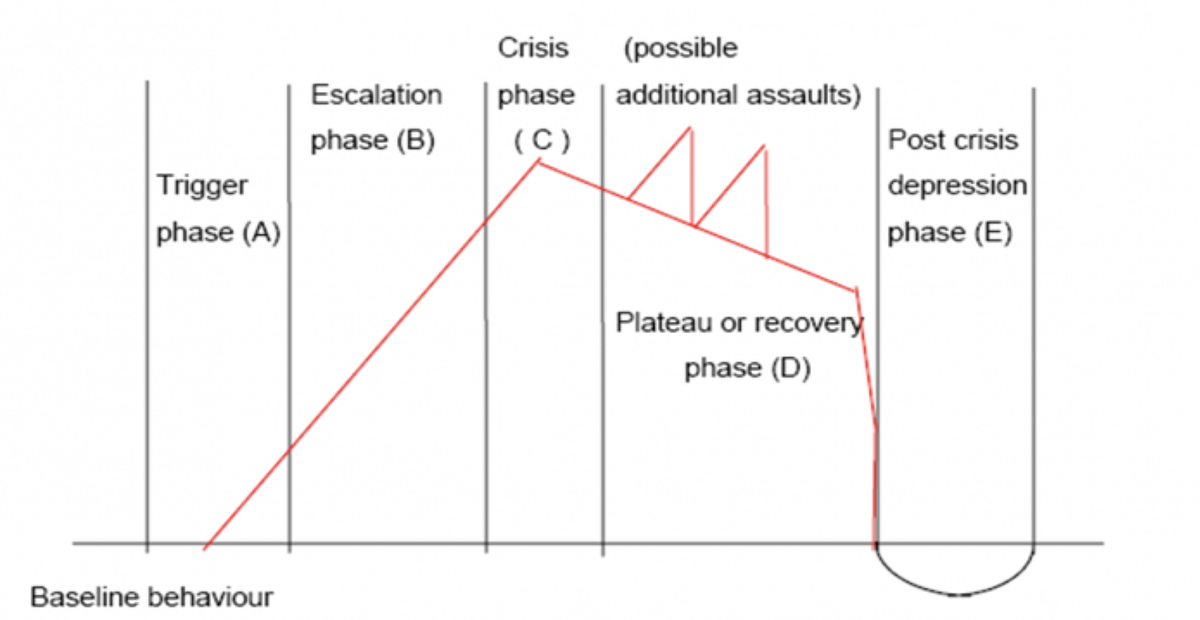

- The emotional arousal cycle has five phases: trigger, escalation, crisis, de-escalation, post-crisis depression.

- Anger can be considered both a primary and secondary emotion. As a secondary emotion it may be masking other important emotions that need to be explored. As a primary emotion, it acts as a healthy indicator of injustice and the need for change.

Unhelpful Emotional Expression

While there are no negative emotions, not all forms of emotional expression are helpful. It is important to remember that it is not the feeling that is the issue, rather, it is the way in which someone might transform or communicate that feeling which can be dysfunctional or harmful. Emotions can become problematic for several reasons:

- Emotional under-regulation (the person is overwhelmed by their emotion)

- Emotional over-regulation (the person is avoiding, numbing out, or shutting down their emotions).

- Maladaptive emotion responses (past traumas can lead to emotional “blockages”).

- Secondary reactive emotions (covering up important emotions with other emotions).

- Instrumental emotions (displaying fake emotion for others).

Emotional Regulation

Emotional regulation is necessary when we are dealing with too much or too little emotion. The capacity to self-regulate emotions is influenced by our early experiences in infancy and attachment style. If we had a secure attachment with a caregiver who modelled healthy ways of responding to emotions and helped us to understand our feelings we are better equipped to regulate our emotions. Emotional regulation does not mean changing or diminishing the way we feel. It is about being able to experience emotions at a level that we are able to cope with and feel in control. Emotional regulation requires practice and the development on various skills including the ability to:

· Notice our feelings

· Identify them

· Access our emotions

· Heighten our feelings

· Tolerate or ‘sit with’ our feelings

· Contain our emotions

· Gain distance from our feelings

Tips for developing these skills will be covered in the wellbeing and coping skills topic. One helpful way to think about emotional regulation is “the window of tolerance”.

Emotional regulation is our ability to maintain a level of emotional arousal that we feel in control of and able to cope with.

The Window of Tolerance

The window of tolerance, first developed by Dr. Dan Siegel, describes the optimal zone of emotional arousal (or emotional activity) that still allows us to function in a healthy way during our everyday lives. When a person is operating within this ‘window’, then they can cope with their emotions. If we are unable to regulate our emotions, we go into a state of hyperarousal. In this state we feel out of control in response to our emotions and we may display explosive displays of anger or fear. Hyperarousal coincides with the stress response where we enter a fight or flight state. Hypoarousal is the opposite of hyperarousal. In this state our emotions are over-regulated. We shutdown in response to our emotions and may feel withdrawn, quiet, and disconnected from the world around us. In this state we may appear to have no feelings at all.

The window of tolerance is not a static concept. Our window of tolerance can shrink and grow throughout the day and across the lifespan. There are lots of things that affect the window of tolerance such as our diet, levels of exercise, stress exposure, who we are with, the environment we are in and the amount of sleep we have had.

There are also long-term factors affecting our window of tolerance. For people who have experienced some sort of trauma, they often struggle to exist within this healthy window of emotional arousal, as it has become shrunken. This means that people are more easily overwhelmed by stress and cannot effectively manage their emotions. In response to something upsetting, they quickly stray into a state of hyperarousal or hypoarousal and find it harder to return to their window of tolerance. However, the more we practice emotional regulation and look after our emotional and physical health, the more our window of tolerance can grow. By enlarging our window of tolerance, we can increase our capacity to experience our emotions in a healthy way, without feeling out of control or disconnecting from reality. When discussing the window of tolerance, we can also refer to the zones of regulations where hyperarousal equates to the “red zone”, hypoarousal as the “blue zone” and the window of tolerance as the “green zone”.

The Emotional Arousal Cycle

The emotional arousal cycle is a useful way of mapping the escalation of emotion to the point where we are unable to regulate it. The emotional arousal cycle stems from “The Assault Cycle”, introduced by Kaplan and Wheeler (1983) (and later developed by Breakwell, 1997) as a way of thinking about an episode of aggressive behaviour that may be physically violent. The five stages are the trigger, escalation, crisis, recovery or de-escalation, and post-crisis depression.

Similar models are often used in relation to anger management and have been referred to as the aggression cycle or anger cycle. While initially proposed as a model for anger and aggression, the cycle is applicable to the escalation of any strong emotion triggered by an event and resulting in emotional dysregulation. We can think of it as a trigger event that causes emotional escalation to the point of becoming overwhelmed. Emotions may include anxiety, fear, anger or a combination of many emotions that we are unable to regulate. It is therefore more accurate to consider it as an emotional arousal cycle rather than an assault cycles, especially as the “escalation” and “crisis” phase are experienced and expressed uniquely. The emotions may be internalised in the crisis phase or manifest as distress behaviours rather than outward aggression.

(Kaplan and Wheeler, 1983)

Stages of the Emotional Arousal Cycle

The Trigger Phase is an event or stimulus, internal or external, that causes emotional escalation. It can be a person, place, situation, feeling or thing. It may be a perceived threat or feelings of frustration.

The Escalation Phase is the body preparing for the crisis phase. Physical and behavioural warning signs may be present with growing levels of emotional arousal. At this stage, de-escalation is possible and early intervention or self-soothing can prevent the crisis phase.

The Crisis Phase is the peak of emotional arousal and is likely to be accompanied by an emotional release that may seem explosive. In this phase, the person is now in a fight/flight state and may struggle to calm back down. They are unable to apply rational thinking and they are likely to be unable to respond to interventions that may have worked during the escalation phase. Different strategies for exiting the crisis phase may work for different people but in general we need time and space to come out of the crisis phase before we are able to engage.

The De-escalation or Recovery Phase occurs as we come out of the crisis phase and are beginning to calm down. This can take a prolonged period of time and is not a linear process. We may experience fluctuation of escalation and de-escalation and may have a second crisis peak.

The Post-Crisis Depression Phase occurs after de-escalation and is characterised by a drop in energy. We my feel emotionally and physically exhausted after the incident. This phase may involve feelings of shame, guilt, regret and sadness around the behaviours associated with the crisis phase, our perception of ourselves, and how we believe other perceived the situation.

Following these five stages, and when the person is back in their window of tolerance, it is important to reflect on the event, what was triggering them and what could have been done in the escalation phase to prevent the crisis phase.

What is Anger?

Anger is a complex emotion that is often associated with hyperarousal and emotional escalation. It is important to firstly distinguish between anger and aggression. Anger is an emotion while aggression is a behaviour that may or may not stem from anger. It is okay and healthy to feel anger, it is not okay to behave in an aggressive way. There are other ways that we can express and explore anger without aggressive or violent behaviour.

We can think about anger in two different ways. Some argue that anger is a secondary emotion that stems from primary emotions such as fear, rejection or anxiety. It can become problematic if anger is masking the primary emotions and these are left unexplored. When someone is displaying behaviour typical to anger, or is in a state of hyperarousal or emotional crisis, it is important to consider that they may actually be experiencing fear or distress and may need comfort and reassurance in order to calm down.

While this form of anger can be problematic, anger is also considered to be a basic human emotion. In its primary form, it is healthy to feel anger and it can act as an indicator of injustice. Often it is alerting us to something that needs to be changed. Anger needs to be felt and acknowledged. If the causes of anger are left unaddressed, it can fester into other uncomfortable emotions or unhelpful expression.

Anger is closely to our needs, values and sense of security. When someone is angry, consider if their boundaries, ethics and values are being compromised; if a need is not being met; or if they feel they or a loved one are under threat.

References and Further Reading

- How to Help Your Clients Understand Their Window of Tolerance. NICABM, 2019.

- Information Note: Window of Tolerance. Education Scotland.

- Survival skills for working with potentially violent clients by S.G. Kaplan and E.G. Wheeler. APA PsychNet, 1983.

- Coping with Aggressive Behaviour (Personal and Professional Development) by G.M. Breakwell, BPS Blackwell, 1997.

- Why is Anger Important? Chelsea Psychology Clinic.