Professionals and Practitioners

This digital resource tells the story of how our brains interpret the world around us and how this translates in our bodies, emotions and behaviours. It has been designed to be used by professionals working with young people interested in learning more about the science of conflict and boosting their wellbeing.

What Attachment?

Summary

- In psychoanalytical terms, ‘attachment’ means an ‘emotional bond’ and ‘lasting psychological connection between people’.

- Our first attachment relationships act as a ‘blueprint’ for our experiences of all other relationships as we grow up.

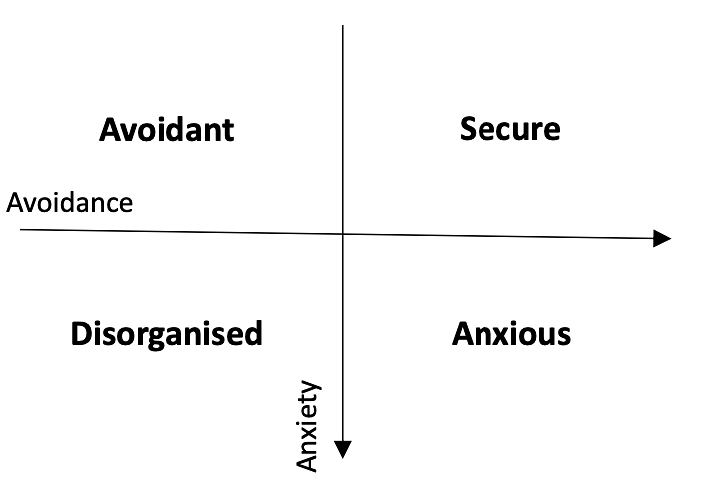

- There are four main attachment styles: Secure, Anxious, Avoidant, Disorganised.

- A baby who experiences a secure attachment with their mother will grow into a child who trusts that other people will be able to meet their emotional and physical needs.

- A baby who experiences an insecure attachment (anxious, avoidant or disorganised) may find it more difficult to for and maintain meaningful relationships and express their feelings in a healthy way.

- People rarely have one style of attachment; over time, we experience a mixture or different intensities of attachment style, and with the right support, we can change our attachment styles.

What Is Attachment Theory?

The psychoanalyst John Bowlby developed ‘attachment theory’ in 1958, based on his work in a Child Guidance Clinic in London, treating children with mental health disorders. Bowlby argued that much of our behaviour and emotional patterns can be explained by our early life experiences.

Attachment can be understood as an ‘emotional bond’ and ‘lasting psychological connection between people’.

Bowlby suggested that our first attachment relationships act as a ‘blueprint’ for our experiences of all other relationships as we grow up.

According to attachment theory, human beings are biologically ‘pre-programmed’ to establish attachments with other people, as social connections have helped humans to survive millennia from the dawn of humanity to the present.

Human babies are born with an innate need to attach to one main caregiver in their very early years, as a primary close attachment means survival is more likely. Babies naturally seek closeness to their caregivers and feel more relaxed in the presence of adults who care and love them. Human infants have evolved to exhibit behaviours that encourage caregiving from people around them. These behaviours include crying, smiling, crawling, and even having a ‘cute’ appearance.

The first five years of a baby’s life are a critical period for forming a primary attachment.

A bond between a baby and caregiver may not form because the adult cannot give the baby enough emotional responsiveness, because they are physically absent, or because they are unable to provide appropriate love and affection. This may be for a variety of reasons.

If an attachment is not formed during the first five years, then the baby may grow into a child and adult who struggles to form meaningful relationships with other people, and may struggle more with low confidence and self-worth.

Our first attachment relationships act as a ‘blueprint’ for our experiences of all other relationships as we grow up.

Why Is Attachment So Important?

A positive attachment between a baby and a caregiver allows them to develop:

· Healthy brain growth

· Ability to trust others to meet their needs.

· Self-worth and confidence

· Ability to be left alone without distress or fear of abandonment

· Ability to explore and learn about the world without anxiety

· Know that they are deserving of love and affection

Healthy social, emotional and brain develop in early childhood through secure attachments allows the child to grow into an adult who is able to form healthy relationships with confidence and self-worth more easily.

Different Attachment Styles

We develop different attachment styles based on how we experience relationships with caregivers in our early years. There are four main attachment styles.

Let’s look at each of these styles in more detail.

1. Secure Attachment

Cause of secure attachment:

- Close and healthy bond with at least one adult caregiver in infancy who was paying attention and responding to their emotional and physical needs. This could include feeding the baby when it is hungry, smiling at each other whilst playing, or offering loving physical comfort when upset.

Infants with secure attachment:

- Display distress when separated from their caregiver, but are able to quickly calm down and relax once reunited.

- Can confidently enjoy exploring their surroundings, without feeling anxious that their loved ones will abandon them.

- Are cautious of strangers, but will relax if the new person shows warmth and signs that they can be trusted.

Adolescence/Adults with secure attachment:

- Enjoy connecting with other people in an open and self-assured way.

- Can express a need for love and affection.

- Form healthy and meaningful relationships easily where they feel valued and supported.

- Have a sense of self-worth and know that they are worthy of love and affection.

- Have trust that they will not be abandoned or mistreated.

- Offer care and support to others comfortably.

2. Anxious Attachment

Cause of anxious attachment:

- Attachment with caregivers who are not able to consistently and reliably give the baby attention and meet their emotional and physical needs. It may be that parents were struggling with mental health or relationship difficulties of their own, and were subsequently unable to be fully present to provide consistent loving care to their baby.

Infants with anxious attachment:

- Display distress when separated from their caregiver. It is difficult to comfort them even when reunited.

- Can be clinging to their attachment figures

- Appear more anxious and exploring less than infants with secure attachment.

- Are cautious of strangers.

- May have difficulty interacting with peers.

Adolescence/Adults with anxious attachment:

- Fear that other people will abandon them.

- Fear that their needs for emotional and social connection will not be met.

- Often fell anxious in romantic relationships

- Often feel overwhelmed by their emotions and unable to regulate them in stressful situations

- May interpret ambiguous situations as negative, due to early experiences of people being unreliable.

- Can become emotionally distressed and may display ‘protest behaviours’ such as shouting, throwing things, or giving their partner the ‘silent treatment’ if they perceive a threat of abandonment or feel that their partner is acting negatively towards them.

- Incorrectly view themselves as to blame as they are “unlovable”.

3. Avoidant Attachment

Cause of avoidant attachment:

- Attachment with caregivers who were consistently unable to meet their needs for attention and care. This might include ignoring the babies crying or displays of emotion, becoming angry if the baby becomes distressed, or shames the baby for displaying emotion.

Infants with avoidant attachment:

- Remain calm when separated from the caregiver, but avoid contact with them when reunited. The infant is distressed by the separation but unable to show it.

- Are cautious or avoidant of strangers.

- Struggle to connect with peers.

Adolescence/Adults with avoidant attachment:

- Struggle to display vulnerability and express their thoughts and feelings.

- Struggle to establish close social connections, preferring to keep people ‘at arm’s length’

- Often detach from their emotional experience and may appear aloof and unfeeling to others.

- Believe that people are not capable of satisfying their unmet need for love and closeness, so remain distant from others to avoid the pain of expected disappointment or rejection. They may also believe they are “unlovable”.

- Expect people to let them down.

4. Disorganised Attachment

People with disorganised attachment style experience a mixture of anxious and avoidant attachment style tendencies.

Causes of disorganised attachment

- This attachment style is least common and typically a result of childhood abuse and neglect.

- Attachment with caregivers who were seen as frightening and unreliable.

Infants with disorganised attachment:

- Are forced to depend upon an adult who is also a cause of fear and harm.

- Display both avoidant ways of managing distress, as well as anxious strategies to gain attention and affection.

- Also experience dissociative symptoms like physically freezing or psychologically detaching from reality in response to stress.

- Display distress when separated from caregiver but continue to display distress when reunited. They may run to the caregiver before running away again in a fear response.

Adolescence/adults with disorganised attachment:

- May appear confusing to other people, as their behaviour seemingly randomly changes from anxious and emotionally explosive, to withdrawn and emotionally shutdown.

- Struggle to feel safe or calm in relationships.

- Are more likely to seek out relationships that are exploitative or otherwise harmful, as this feels familiar to them.

Final Thoughts

People rarely exist in a state of being exactly one or another different style of attachment. Instead, imagine that attachment style exists on a spectrum, with people experiencing a mixture or different intensities of attachment style.

It is important to recognise that while attachment in early years has a significant effect on our relationships in later life, it is not impossible to change our attachment style. Recognising which attachment styles we show tendencies of, can help us to identify behaviours that may be making it more difficult to form relationships. Support, such as therapy, can help the brain heal from trauma and redefine our attachment style to develop healthy relationships in adulthood despite adverse child experiences.

References and Further Reading

- What is Attachment Theory? Bowlby’s 4 Stages Explained by Courtney E Ackerman. Positive Psychology, 2018.

- What is Attachment Theory? The Attachment Project, 2023.

- What is Attachment Theory? by Kendra Cherry. Very Well Mind, 2023.

- Attachment and Child Development. NSPCC Learning, 2021.

- Attachment. Psychology Today, 2023.

- The Trait That ‘Super Friends’ Have in Common by Marisa G. Franco. Atlantic, 2022.

- Attachment Styles and their Role in Relationships. The Attachment Project, 2023.

- What Attachment Styles Can – and – Can’t Explain by Allie Volpe. Vox, 2023.

- Infant-parent attachment: Definition, types, antecedents, measurement and outcome by Diane Benoit. National Library of Medicine, 2004.